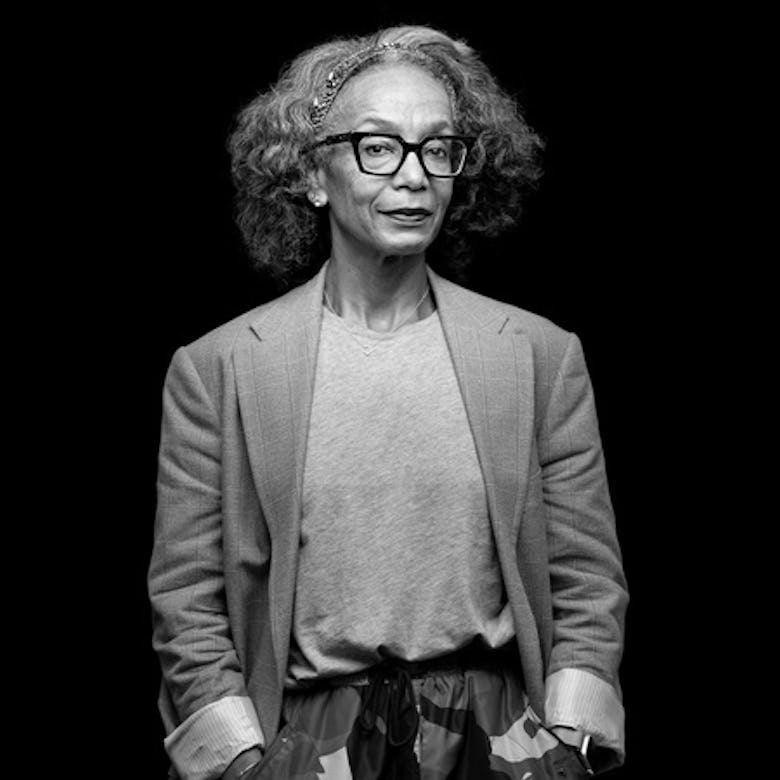

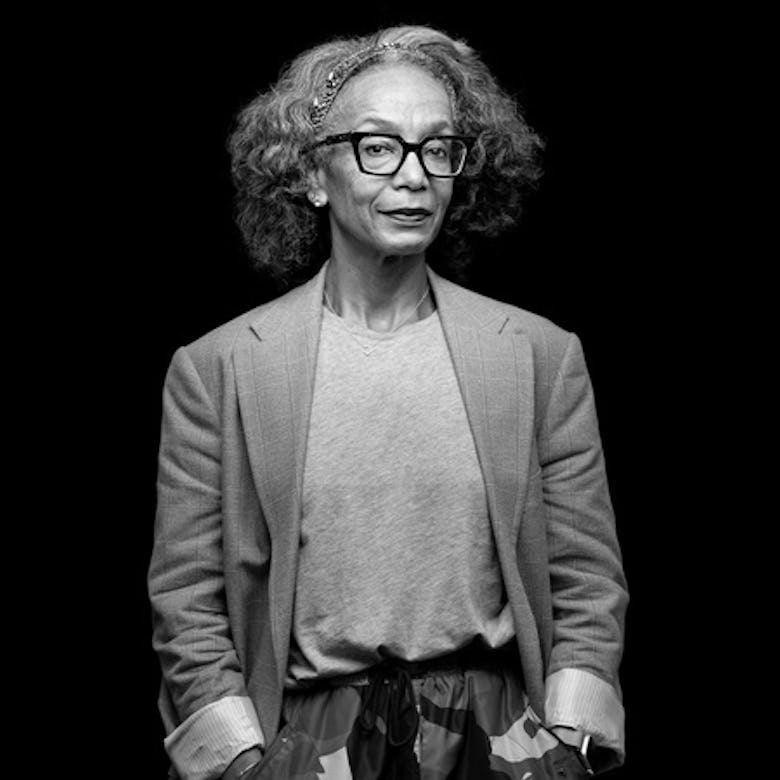

The Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Robin Givhan can still remember her “first, most searing memory” about designer Virgil Abloh, who changed the fashion industry as we know it in the 2010s and is the subject of Givhan’s latest book, Make It Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture With Virgil Abloh. It was 2015, and Abloh’s brand, Off-White, was up for the LVMH prize after he’d spent years as Kanye West’s creative director. “I got to the booth, and there was this scrum around it—phones and video cameras everywhere—but mostly because Kanye was there,” Givhan told W ahead of the book’s release. “He’s pulling stuff off the racks and hyping up his guy, which is really lovely, except he’s sucking up a lot of the oxygen. I’m thinking to myself, ‘I know you’re a famous rapper, but can you move over?! I really want to talk to Virgil!’”

Make It Ours, Givhan’s follow-up to her 2015 debut book The Battle of Versailles, was informed by a deep curiosity about the man who created relentlessly up until his death at age 41 from a rare form of cancer. That included bouncing from Pyrex Vision to Off-White c/o Virgil Abloh to redesigning a slate of Nike’s classic sneakers, all the while changing the way we talk about style. The book is filled with industry anecdotes that’ll thrill any fashion fan, covering Abloh’s early days making t-shirts in Chicago to scaling the ranks at European houses and becoming the first Black creative director at Louis Vuitton men’s.

Most importantly, the book explores Abloh’s impact on fashion, and the way he appealed to “the desires and anxieties of young men,” as the author and Washington Post fashion journalist puts it. “I wanted to be thoughtful and fair about his work, but I also didn’t want to overshadow this other legacy he had left, which had nothing to do with the shape of the clothes, but had everything to do with the meaning he injected into them.”

Virgil Abloh did so many things in his life: fashion design, DJ’ing, producing. How did you find one specific lane of his to focus on?

There’s a book to be written about the many, many collaborations he did. And there’s a book about the inner psyche of Virgil, written from the point of view of a confidant. But I was intrigued by the way he moved through fashion. It was fascinating to hear from people who were his contemporaries, some of whom were big fans, and some of whom were lukewarm to his work. It was also interesting to get a sense of the surrounding context that made him: this kid in the Midwest who was into these really disparate things.

In the book, you talk about how Abloh was described in the media as “the son of Ghanaian parents” rather than African American or Black. What’s the significance of the distinction there?

I was always curious about that. To some degree, it’s giving you more specific information. But at the same time, it’s completely correct to refer to him as African American. It’s not like he himself is an immigrant. There’s this tension between people who are recent immigrants from an African country, or [whose parents are], versus those whose histories go back to enslavement. The unfortunate hierarchy in the U.S. is that you are on a slightly higher rung if you are Ethiopian or Ghanaian or Nigerian, versus simply African American. And that’s very sad. Immigrants are taught that the first thing you want to do is make sure you don’t get lumped into just being Black, because that will make your journey much more challenging.

I talked to a guy whose parents were also from Ghana, and he had had a long conversation with Virgil about that shared background. I said to him, “My parents would always say, You have to be twice as good—you have to really be accomplished in order to get just as far.” And he told me his parents would never say that to him, because you already know that you’re twice as good. It’s a subtle distinction, but a powerful one. You see that in the way Virgil operated, especially when contrasted against his relationship with Kanye West.

There is a whole section about Kanye in Make It Ours. Was it strange, writing about “the old Kanye,” when he’s now Ye and using very inflammatory language?

Yeah, there were a whole bunch of footnotes to this book [laughs]. In many ways, I couldn’t write about Virgil’s fashion journey without writing about Kanye. But I was happy the Kanye portion was contained to a period before he became Ye, before his antisemitic rhetoric started to blow up. It was sad. Because certainly during that Chicago period, Kanye’s coming off these two amazing albums, the talent is boiling. There’s extraordinary ambition and confidence and desire, he is sweeping up people in this storm, and he is frustrating as ever—because he did have these magpie, barnacle-like tendencies. But at the same time, you can see how infectious that ambition would be. It was also an instructive experience, because as many people pointed out, there was a big difference between the way that Kanye dealt with criticism versus the way that Virgil did.

Do you believe the fashion industry is looking for the next Virgil Abloh, or was his life and work simply lightning in a bottle?

Both of these things are true. There were many aspects of Virgil that were lightning in a bottle. I hope that fashion is not looking for another Virgil, because that would be playing into the old tropes of finding another version of the thing you already have. Fashion needs to be just looking for another creative.

I wonder if you’ll play a little “fantasy fashion” with me. Who would you like to see as the creative directors at Fendi, Proenza Schouler, and Marni—all houses that are currently without a head designer?

I heard Fendi was talking to Willy Chavarria; I don’t even know if I can be objective here, because I love Willy so much. I talked to him for the book, and he told me that when Virgil was alive, Willy was on the record of not being a big fan of his work—as, honestly, were quite a lot of designers. But Willy recognized the impact that Virgil had on the community. He said something like, “It inspired me to have that kind of impact on people with my work.” So I will go with the rumors and say, Willy for Fendi!

For Proenza, in keeping with the history of the house, it should be some young designer who’s a girl or boy wonder, fresh out of design school, that I don’t know about, but I might see at a Parsons show.

And because she is freshly on my mind, Rachel Scott, from Diotima, could be really interesting at Marni. I would love to see a woman take that, because Francesco Risso did a wonderful job, but the industry needs to cast the net wider. I feel like executives want to, in theory. But they keep going to the same well. I get it, there’s a pipeline. But when the pipeline is narrow, it behooves you to look at different pipelines.

You approach this book in a very journalistic manner, but I wonder how you personally felt the day you found out Abloh had died.

I was certainly shocked. I was sad that this person, who is obviously so young and so talented, had passed away. And of course, when that happens and you’re in the newsroom, you start thinking, What did his career mean? What do I want to write about this?

Virgil had the ability to make a lot of people feel like they were his friend, even if their only encounter had been via two DMs on social media. I was not someone who felt like Virgil was my close friend. So when I saw that outpouring online—people talking about him as if someone they had a deep relationship with had passed away—I was surprised and curious. I didn’t quite get it. That disconnect was one of the first seeds that were planted for this book.

You’ve done some politics reporting since re-joining the Post in 2014. How has writing about the White House influenced the way you approach fashion journalism?

On the one hand, it has encouraged me to look at the ways in which creative people speak and rise to the moment. Sometimes, designers don’t even need to be overtly political. It can simply be in their refusal to prejudge something. That’s a powerful thing to do. I was talking to one designer who said they wanted to “avoid the contempt of the unknown.” Essentially, that I should constantly remind myself to not be disdainful of something that I’m not fully understanding. That’s a wonderful way of approaching your work in fashion, but it’s also a great general lesson—no preemptive disdain.

The other thing is, I don’t think there is a greater need for the sheer beauty, joy, and pleasure that can come from fashion in this moment. I hope designers just give you the most irrationally beautiful thing of desire. Because we could use it.